I have a new book out. It's not the most brillant cover or blurb but that doesn't mean the book's contents aren't bad. It takes place on a fantasy world with a 1940s-50s level of technology.

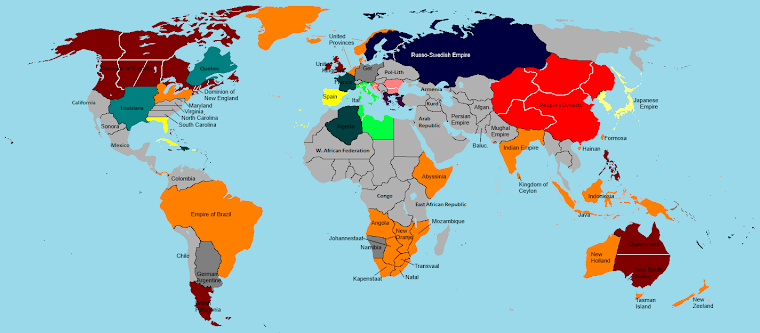

An Alternate History of the Netherlands is a little something I've been working on since 2008, and it follows the evolution of a world in which the Dutch were not divided along religous lines during the Dutch Revolt of the last 16th Century. Along with An Alternate History of the Netherlands, some of my other projects, such as the Stardust Sequence (since 2000) and the Wing Commander reboot (since 2010) may make appearances.

The World Today

Earth in 2013

Saturday, December 12, 2015

Sunday, April 5, 2015

The Unofficial Company

The suspension of civil government did not stop every officer of the law in the former Confederacy. In Texas, as lawlessness in the countryside grew, out of work lawmen banded together to establish the Unofficial Company of the Texas Rangers. Unlike other vigilante groups, which were often thinly veiled pro-Confederate gangs, the Texas Rangers before and after the war swore allegiance to the State of Texas. To many of the lawmen it mattered to less union Texas belonged than having peace and security within their State.

Unlike those same organizations, the Unofficial Company consisted of actual, trained police officers. A few were Rangers before the Great War, where some volunteered for 50th Texas Cavalry, a unit which saw plenty of action in Texas, Oklahoma and Jefferson. Others were policemen and college graduates with aspirations to join the prestigious ranks of the Rangers. In Texas, there was no law enforcement agency more respected than the State’s own policing force. It was also one of the oldest policing forces in the South, with roots stretching back to the short-lived Texas Republic.

The Unofficial Company ranged throughout western Texas, where occupation authorities paid little attention. The US Army’s primary concern in Texas was keeping order in the cities and stamping out any pro-Confederate movements. Crime in the western counties, especially when it did not pertain to the occupation forces, was left to an undermanned county sheriff department, a force so disarmed that they were only permitted to carry sidearms and that was a concession for self-defense.

The Rangers were not bound to any arms limitations. Most carried sidearms, such as the Yankee-designed Colt .45 or Tredegar .38 revolver, while many carried hunting rifles, shotguns and heavier weapons purchased in Kansas and Nebraska. In the 1920s, even in the border States, civilian purchase of firearms was not a difficult task. Often all one had to do was walk into a hardware store and select from a range of weapons. Catalog-ordered weapons, such as the Thompson submachine gun were purchased through sympathetic Kansan supporters. As lawlessness increased in western Texas and the Oklahoma panhandle, bank robbers occasionally took up residence in safe houses inside southwestern Kansas. The smart ones made certain to not as much as jaywalk while inside Kansas’s borders.

One of the ongoing battles in Texas was between the Rangers and rum-runners, or rather tequila runners from across the Rio Grande River. Veterans residing in Brownsville and other border towns established contacts in Mexico, purchased large quantities of alcohol and smuggled it across the border. The Temperance Movement made as many roads into Texas as it had the Midwest, eventually closing the State to liquor in 1922. Most of the voting population lived in the eastern, agricultural region of the State. Those who lived in the western and southern counties were not legally dry as only a handful of the counties passed prohibition laws. All of them did, however, outlaw other drugs such as morphine.

The Unofficial Company was divided on a personal level over the subject. On one hand, they did not believe any government had the right to control what one did or did not drink. That was a personal choice and for a governing body to decide it was plainly unjust. As the Founding Fathers said, the citizen had a right and duty to oppose unjust laws. The Mestizo Rangers knew of unjust laws on a more personal level. Though their status in the racial hierarchy of the Confederacy was not set in stone like those of Blacks, there was still the custom of racial division. Texas law made them equal to Whites in the eyes of the law but there was always a feeling they were on a low rung on an unofficial level.

However, as an agency that prided itself on upholding the law, no matter how unjust, they could not simply ignore it. With limited resources, they could and did prioritize it. The criminals were not those who drank alcohol but the violent thugs who smuggled it across the border. Naturally organized crime was not as open to free trade and competition as other facets of society. Each gang wanted a monopoly over the border crossings. The two big players in Brownsville, the Hernandez Family and Jamison and Associates, fought for control of the city and border crossing. It was more than a simple business dispute as Reginald Jamison was brother to infamous SOC leader Leopold Jamison and funneled part of his gang’s profits into funding the SOC.

One would think having an organization such as the Sons of the Confederacy backing them that Jamison and Associates, the legitimate sounding organized crime syndicate, would have no problem in controlling the border. Enforcing an unpopular law was quite a different matter than hunting down domestic terrorists as Reginald was well aware. He and most of the Jamison, while proud of their relatives work also distanced themselves from him less they fall under the scrutiny of the occupational authority. Given that the scuffle in Brownsville was also between different races any overt act on behalf of the SOC would have brought the US Army down on the place in a hurry.

Without them, it was a small matter by Jamison and Hernandez to pay off the garrison commander, who was more interested in stopping the smuggling of weapons or the SOC’s hideouts across the border. Major Thompson still had to bust up a smuggling ring from time to time, to keep up appearances in the eyes of his superiors, but for the most part the Army stayed out of the gang war. Some of the Rangers would not have minded watching the gangs kill each other off. However, as with so much gang violence, there was always those innocents caught in the middle.

The Unofficial Company took it upon itself to battle both of them and to protect and defend the civilian population. As with local law enforcement and the Army, both gangs tried to buy off the Rangers. To their dismay, it did not work. The Unofficial Company was not in the business for the pay, for they had none. They volunteered because they believed it their duty to uphold the law. Introduction to organized crime strengthened that resolve as it weeded out the corrupt Rangers from the idealistic ones.

The incorruptibility of the Unofficial Company did not escape public notice. So much so, that even General Haise, commander in Texas between 1921-24, took to calling them ‘untouchable’ to the greasing palms of bribery. He considered lobbying Congress to allow him to reinstate the Rangers but ultimately decided against it. As they stood, volunteers fighting for their principles, they would be stronger than a genuine state law enforcement agency, susceptible to bribery and corruption. Better to let them do their thing and not have to pay them. It would be one less problem for the Army. It would be up to his successor to reinstate them and then as a means to reign them in. At times, the vigilantes could be as bloody as the criminals they fought, as the hanging of more than one gangster proved.

Sunday, March 22, 2015

Robber Barons

When the Confederate elite fled the South they did not leave empty handed. They could not take their slaves with them, for any destination they wished to immigrate to had already outlawed the institution, but they could transport more liquid assets overseas. Privately owned banks throughout the South vanished between 1916 and 1917 as their owners closed down shop and absconded with the assets. A few of these were apprehended but even then the money was confiscated by occupation authorities and if it ever saw its lawful owner again it was pennies on the dollar.

The Bank of Georgia, owned by the State of Georgia, was the largest of the vanishing banks. In November 1916, when it closed its doors, its central bank in Atlanta held more than a million dollars in cash and gold. With the fall of the C.S.A., paper currency was all but worthless. The gold was another matter. It was swooped away by the bank’s regional manager, Reginald Louis, who promptly fled to New Grenada with two hundred thousand dollars worth of gold. The fleeing bank managers earned the disparaging name ‘Robber Baron’ for once they robbed the bank they lived like barons in a foreign land off the earnings of honest citizens.

Oddly enough, the small time bank robber was not condemned, for they struck at the Northern banks that filled the void. These were seen by Southern civilians as ‘the enemy’. A number of banks, Wells Fargo and US Bank being the largest, lent freely to would be farmers and those civilians trying to rebuild their lives. They were equally quick in seizing assets when bills were not promptly paid. When average citizens struck back against the bank, they were hailed as folk heroes.

The most notorious of them was John Dillinger, who was not even a Southern. Dillinger started his criminal career in Indiana, robbing a grocery store in Mooresville. With the whole of fifty dollar he managed to escape with, he fled Indiana for Alabama, one step ahead of the law. It was in Huntsville that he robbed his first bank in 1920, followed by another in Decatur the following year and Montgomery in 1922. In Montgomery, he was cornered by occupation authorities, narrowly escaping in a shootout over the corpses of two of his fellow gang members.

Thinking he would be safe in Florida, he high-tailed it to the State boundary. Unlike civilian police, the United States’ Army held a world-wide jurisdiction and word of his escape quickly reached authorities in Pensacola. Instead of striking the first bank he saw, Dillinger managed to get in contact with a friend from his Navy days, who hid him throughout 1922. His friend, Jim ‘Mackey’ McDonald had friends of his own in high places. He was an enforcer in the Jackson Company, a fancy name for an organized crime syndicate operating out of Pensacola.

The Jackson Family, headed by Thomas Jefferson Jackson former CS Army Sergeant and his brother Robert, controlled the flow of alcohol and other drugs from Cuba and beyond into the Deep South. They were reluctant to take on a face as familiar to the law as Dillinger, despite his abilities. One did not stay in the smuggling business long without remaining low key. They did agree to smuggle him to Havana where he could lay low. Unfortunately, the temptation to rob banks was too great. A month after arriving in Havana, Dillinger targeted a branch of US Bank in neighboring Jacksonville, where he was killed in a shootout with the bank’s hired guns.

Sunday, March 8, 2015

Temperance

Long before the start of the Great War, much of the Deep South were dry States. That is, the production, transportation and selling of alcohol was banned. Totally prohibition was a goal of many morally self-righteous crusaders in Alabama or Florida but it was against the ways of life in the western States and in Cuba. In Texas, for example, only some of the eastern counties were dry by 1913. Whiskey and tequila were so culturally ingrained in Texas, Jefferson and Sonora that banning them was quite impossible. The same proved true for most of Cuba and rum, though the city of Jacksonville was nominally dry.

After the defeat of the Confederate States, temperance grew in strength. Crippled soldiers, men who lost limbs and their ability to earn a living began to slowly drink themselves to death. Even those men who came back from the front physically in tact suffered from a rising epidemic of alcoholism. The wives of these veterans grew tired of their husbands spending their rent and grocery money in the saloon on Saturday night. Even in supposedly dry States, it was not that difficult to get ones hands on bath tub gin. Or, after occupation began, purchasing it from Yankee soldiers who ignored the local laws.

As civilian government were still suspended in 1918, it was impossible for any States to ban alcohol. With city and county governments still functional, albeit under close Union supervision, the Crusade against Drunkenness decided to tackle the problem from below. In 1919, Tennessee managed to ban alcohol by making every county dry. Virginia followed suit in 1920. Even the western States saw some of their counties grow dry. The growing movement began to protest the occupational authority as well.

Still under martial law, local commanders were well within their rights to break up any protest with little or no reason. The new Hughes Administration issued the ordered that provided the protests did not turn violent and in no way impeded the Army then they should be tolerated. After all, it was better to let the Southerner vent their steam in protests than keep it bottled up like gasoline fumes, waiting for a spark to ignite it. Orders were issued from military governors, forcing soldiers to respect local laws. This did not mean they ceased drinking on base, only that they would now be punished for selling liquor to civilians.

Punishment was no deterrence for privates with salaries of thirty-five dollars a month earning two hundred on the side for selling a few bottles of whiskey. As with any extralegal activity, the foolish ones were the first to fall. Any private with a gold pocket watch was suspect. The more cunning and enterprising enlisted personnel began to organize themselves, pay off local authorities and above all keep a low key. To accommodate the extra income, unauthorized or crooked banks opened their doors to the Yankee.

Alcoholism was not confined to the South. The North had its fair share of cripples, physically and mentally. The rise in consumption was not immediate as most soldiers remained on occupation duty. As National Guard units demobilized and returned home, saloons and pubs began to see record business. Out of work veterans had little else to do with their time than drink it away.

The temperance movement took hold in the Midwest, with Kansas, Nebraska, Lakota, Iowa and Illinois passing prohibition laws in the 1920s. With the power of hindsight, modern scholars often criticize these lawmakers, saying it was they who allowed organized crime to grown from petty thugs to a multi-State enterprise. There is some truth to it but in the context of the age, alcoholism among the nation’s youth was a very serious problem. These young men, for most veterans were under the age of twenty-five, still had their lives ahead of them. Drinking their lives away was viewed as a waste.

When a dry State lived next to a wet one, it almost made the laws moot. The most infamous case was that of Cuba, where vulture capitalists seized control of the rum industry following the end of the war. Profiting off the suffering of the Southern people was one of the prime causes for making the name Kennedy hated so much in the former Confederacy. For the rum runners, it was only a short boat ride from Havana to Pensacola, Mobile or New Orleans. Each of these four cities saw a spike in violent crime as various gangs struggled for domination of the booze trade.

Alcohol was not the only product they had to offer. Among the millions of wounded in the war, some developed an addiction to pain killers. Chief among the analgesic drugs was morphine and later its replacement heroin, which was ironically developed as a non-addictive alternative. Opioid drugs proves a little harder to manufacture than rot-gut booze but its higher price made it a worthwhile investment in the black market expanding across the South.

The 1920s drug trade was conducted not only by those who sought quick riches but also by a number of terrorist organization in the South. The Sons of the Confederacy were quick to get into the business, using the profits generated to purchase weapons and turn them on the Yankees. To their dismay, these Southerners found themselves facing off against other well-armed Southern gangs. Their rivals for the booze trade ranged from former comrades to former slaves. It took only a few weeks of the trade for many Sons of the Confederacy to give up avenging themselves upon the Yankees in favor of quick wealth.

Saturday, February 28, 2015

Two navies, one ship

The War Department captured a great deal of booty following the Confederate surrender, including partially finished ships sitting in shipyards. One of the more famous examples was that of the CSS Ranger. Following the defeat in the Bahamas, the Confederate States Navy was reluctant to send out its remains ships in fleet strength. Instead, they preferred to send out smaller units to conduct hit-and-run raids against their enemies. The large battleships built after the turn of the century were not suited for this sort of combat. Instead, the Confederate Navy ordered a number of quicker battlecruisers constructed for the purpose.

On the day of Virginia’s surrender, workers in the Norfolk Shipyards did their best to destroy ships under construction, denying them to the Yankees. The Ranger was little more than a hull at the time and was ignored in favor of scuttling more complete ships. As such, the U.S. Navy took control of the wreckage at the end of the war and assessed the damage. The hulls could be used, though for what purpose they had yet to determine. The arms limitation treaty forced many of the new projects to be delayed or scrapped altogether.

In 1918, the hull of the Ranger sat in the shipyard, unused and slated for breaking up. That is, until Commander Eugene Ely happened upon the ship. The Great War saw an acceleration of aviation technology, from pusher aircraft that could barely match modern speed limits on a freeway to sleek, aerobatic biplanes and four-engine bombers. The U.S. Army was not the only institution interested in aviation.

The United States Navy organized its own air service. Airplanes were used in patrolling the coast, seeking out raiders and scouting for the fleet. A limited number of float planes saw service, carried towards the battle by modified cruisers and battleships. Hearing of Britain’s construction of an aircraft carrying ship, Ely and other naval aviators pressed the War Department to follow suit. It would make for an excellent scouting platform, and perhaps be used in an offensive manner. For admirals who spent their careers in search of bigger guns, the idea of aerial bombs sinking ships was laughable but it did not detract from the use of scouting.

To cut costs on the first aircraft carrier, Ely and his project team sought out first a ship capable of conversion but when he laid eyes upon the hull of the battlecruiser Ranger, he knew he found his ship. After securing funding, work on the U.S.S. Ranger began in earnest. With the low demand for a peace time navy, three years were spent constructing the aircraft carrier, with numerous U-turns in the design, including ripping out of the electrical system at one point in late 1919. It was not until 1921 that the Ranger was launched. Its first assignment was as a scout for the Atlantic Fleet.

Ranger served as a template for two more carriers, the Hornet and Wasp, launched in1926 and 1927 respectfully. Both were built from similar hulls as the Ranger, albeit constructed copies of the Confederate battlecruiser. The U.S. Navy did not have any purposely designed carriers until the 1930s with the launching of the Constellation, Constitution, Enterprise and Chesapeake. The Admirals complained loudly about the construction of these carriers as they diverted funds from their pet battleship projects. With the changing of America’s Congressional alignment, the budget also shifted to meet more pressing demands. Congressmen of the Labor and Republican Parties asked what was the point in building warship when there was no war on the horizon. It was a question that would come to haunt the United States after Reconstruction but that is another story.

Sunday, February 15, 2015

Peace in the North

While the former Confederate States were to be forcefully brought back into the Union with compliant government, the Roosevelt Administration took a different route in dealing with America’s neighbors to the north. Canada, and its British master, were to be treated as equals at the negotiating table. In 1916, the two sides agreed to an armistice, that is a cease fire. Official peace did not arrive until after negotiations were complete in Halifax. Roosevelt’s primary goal was to regain territory lost in the Second and Third Anglo-American Wars, with the congressional delegation from Washington screaming for the past thirty years over ‘unredeemed Washington’, that is the land west of the Columbia River ceded to Canada in 1885.

The return of northern Maine, the Red River Basin and western Washington were an assumed term that neither side tried to dodge, though a number of Canadian and British settlers in the Puget Sound protested over being left to fend for themselves against the Americans. Along with the return of land, a precondition of the opening of negotiations would require a guarantee of property rights for all people who live in the exchanged lands. Roosevelt did not dispute it, saying that property rights were a sacred American institution.

President Roosevelt, British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour and Canadian Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden met in Halifax during July 1917, to hammer our an agreement between the three nations with the ultimate goal being a permanent peace. For too long the English speaking word was divided against itself. With the C.S.A. no longer in existence there was no reason why a reconciliation could not be achieved. After all, mending the rift between North and South would prove a far greater challenge.

When the treaty was drafted and presented to the Senate, Senators balked at the idea of letting the hated British off so easily. At the very least, the United States should take ownership of all the Oregon Country or Britain’s Caribbean possessions. Roosevelt, not wanting to see his growing legacy as a peace maker destroyed, thundered to a group of Senators in private that the United States Army was already overburdened in the occupation and reconstruction of the South. It was quite impossible to occupy Canada as well, unless the Congress planned on raising more troops and thus raising taxes. With a massive war debt already on the books, the debate over ratification was short. Even then, Senators from Massachusetts, New York and Wisconsin voted against the Treaty of Halifax.

Terms of the treaty are summarizes as the following; 1) The northern border of the United States would have northern Maine, western Washington and the Red River Basin south of the 49th Parallel restored to the Union. Furthermore, the island of Vancouver and adjacent islands would be ceded to the United States without compensation. 2) The Great Lakes would be demilitarized. 3) Canada would be guaranteed right of passage through American Pacific Northwest waters and access to the Pacific would not be hampered. 4) The Grand Banks fishery would be neutralized, allowing fishing vessels from signatory nations free access. 5) Cession of the Bahamas to the United States in exchange for twenty-five million dollars. 6) Free Movement of nationals across the border of the United States and Canada. 7) Rights of citizens in ceded territories would not be abridged. Property would not be confiscated without due process of law. 8) Open (but not free) trade between the United States and British Empire. 9) A pact of non-aggression between signatory nations.

The demilitarization of the Great Lakes struck the United States Navy a minor blow. The success of the Great Lakes Campaign of 1913 was a great source of pride for the Navy, the first real victory in nearly a century, though it would pale in comparison with the annihilation of a Confederate battlecruiser squadron and battleship division in the Battle of Grand Bahama. Overseeing the dismantling of the lake monitors was Admiral Charles Vreeland. The USS Minnesota was towed to Duluth where the State of Minnesota purchased it as a floating museum. The rest of Vreeland’s fleet was consigned to the scrap heap, fated to be broken up, melted down and turned into plough sheers or automotive chases.

The non-aggression article caused a bit of a diplomatic unrest between the United States and its long standing ally Germany. Germany did not have such an arrangement with the British and was concerned that with North America concerned, their only useful ally would renege on Central Powers’ treaty obligations. Roosevelt suggested a similar peace between Britain and Germany, which was not as easy as the peace between Britain and America.

There remained concern in London that the Germans, not defeated in the Great War could still be a threat to the British Empire. Even without the US Atlantic Fleet, the High Seas Fleet would still offer the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet a formidable foe. The United States was on the other side of the Atlantic and had not the ability to occupy Canada. Germany was right next door and did have the potential to invade Britain. Just how successful the invasion would be is another matter. There could not be peace in the North Sea until the British felt secure on their island fortress.

As it was in part the Arms Race of 1900-10 that led to war, the recently returned American Ambassador in London suggested to Prime Minister David Lloyd George a general conference for arms limitation. As the war sunk all of its participants into debt, none could afford any massive military build ups for at least a generation. Even so, Germany and Britain would begin to rebuild if they saw the other as a threat. France was too battered by the war to fight and Austro-Hungary was in a poor state even during the war years. Russia faced its own internal troubles as revolutionaries both Red and White battled against the Tsar.

The first round of talks occurred in February 1918, taking place in neutral Rotterdam. The goal was to limit the size of all participating parties’ navies, a goal that all agreed upon in principle. What could not be agreed upon was the ratio that each nation would hold. Britain demanded the largest proportion, siting its geographical situation and its world-wide empire. American Secretary of State Seymour Loomis countered with the obvious question: would dominion navies be considered part of the Royal Navy or separate. Loomis then went on to point out that Canada was more than capable of defending its own coasts now that it was at peace with its only neighbor.

In order to gain concessions, the British conceded that Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand would retain independent navies with their own ratios. Without such an agreement it was quite possible that the arms limitation talks would have fallen apart as the Kaiser’s representatives insisted on being on par with the whole of the Royal Navy. With a smaller Royal Navy, the British would gain a smaller High Seas Fleet all the while knowing they could call upon the navies of their dominions to aid them if war again engulfed the world.

The delegations met again in Copenhagen in July 1918, this time to set ratios of battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers. Britain with its global empire and the United States with two oceans to defend would have the highest ratios, each nearly being equal to the other. Germany and France, with smaller empires were allocated an equal number with a ratio of 5:3 with the United States and British Empire. The growing Japanese Empire, a minor player in the Great War, was also brought into the talks by their British allies. They would gain a 5:3 ratio in battleships and battlecruisers as well.

The United States objected to a growing Combined Fleet, concerned that Marianas Territory would be threatened. In 1914, an Anglo-Japanese force landed on Guam and Saipan, holding the islands for the duration of the war. It was only British pressure that forced the Japanese out of the islands in 1916. In 1898, following the purchasing of the Marianas from Spain, the United States annexed Midway and Wake, handing them over to the Navy to use as coaling stations. These lesser, nominally unpopulated islands would equally be threatened.

Germany felt the same about its holdings in the Marshalls and Micronesia. Truk fell under British occupation in late 1913, with the British holding them until the end of the war. British occupation of German colonies was used at the European negotiation table to prevent Germany from demanding any of France’s colonies as concessions, though German and American pressure did force France to return independence to Morocco.

The final meeting of world naval powers took place in Versailles in November. With the ratios and tonnage of warships determined, all that remained was to determine a schedule of constructing new ships. Again, the 5:5:3:3:3 ratio was used, though France was in a poor position to achieve its full production. On November 12, 1918, the delegates signed the Treaty of Arms Limitation, popularly portrayed as the ‘Treaty of Versailles’ in American press. It was hoped the treaty, along with the Treaty of Halifax would issue in a new era of peace. It did not take long for the United States Navy to discover a loop hole in the treaty.

Wednesday, February 11, 2015

The Fifth Book.

Lost Cause is now live and ready for purchase. It follows the same arc as Hostile Waters and River of Blood.

From Rifles to Ploughs

Whether they succeeded or failed, the two million people taking part in the redistribution of Southern land had a tremendous impact on the economy and politics of the New South. Of the four categories for free land, no class stood out as a major success. Be they soldier, freedman or poor it was character that made the difference between success and failure. They were all given the same plots of land. What in the 19th Century was forty acres and a mule became in the 20th forty acres and a tractor.

With so many people tacking up the plough, the demand for agricultural machinery skyrocketed. What was done only ten years earlier by hundreds of slaves could now be performed by the property owner and his family. In order to meet this demand, factories churning out armored vehicles and aircraft during the war converted to civilian machinery such as ploughs, harvesters and combines.

During the war years, very little in the way of consumer goods were produced, leaving surviving soldiers with all of their earnings as the Army fed and clothed them. Those who were shrewd and saved every penny easily afforded the machinery, which was at first expensive. With so few tractors to go around and so many farmer demanding them, prices soared through the roof. Of course to accommodate the demand and stay in business, factories had to produce more.

Most of the tractors were produced in States such as Ohio, Michigan and Pennsylvania. The distance added cost and one man sought a means of gaining an edge on the market. An employee of John Deer, William Niederkorn quit the company in 1918 and headed south. Unlike the vulture capitalists, he lacked the funds or political connections to gain control of a formerly State-owned industry. Instead, with money saved over the years and loans from New York banks, he purchased a small, run-down factory in Atlanta, establishing Forty Acres and a Tractor. He hoped taking the slogan of land Redistribution would help with sales.

What really helped with sales was location. It is the key aspect of business. He built in the former Confederacy’s industrial belt, much closer to the demanding market. He took a risk that most of the people purchasing his tractors would eventually pay them off. Not all did but most were able to earn sufficient income from farming to pay their bills. In 1924, Forty Acres grew large enough to purchase a competing tractor manufacturer and double their output. Niederkorn would never surpass his former employer but managed to gain his fortune in the South by honest means.

Those who easily paid off their tractors were the soldiers prudent enough to save their monthly income. At the end of the war, they amassed a small fortune and were able to take their forty to one hundred sixty acre and turn it into a peaceful corner of the world. They were the great successes, churning out crop after crop for the rest of their days. Few of the success stories ever sold their farms, preferring the peaceful country life after three long years of war.

Not all soldiers were so frugal or enterprising. A great number of them wasted their income on gambling, drinking and other vices in and out of the trenches. It was not uncommon for an enlisted man to spend their monthly check on a forty-eight hour leave. They were equally entitled to a tract of land, though when they claimed their land they were forced to seek out loans to purchase equipment. More than half of these would-be farmers managed to make a living, paying back the banks over the next ten years and carving out a home in the New South.

That was not always the case. Not everyone who starts a business succeeds. At the turn of the 21st Century, nearly half of newly started businesses fail within the first five years. The failure rate on farms during the 1920s was not quite that high but it was still significant. Those without the fiscal discipline needed to run a business soon dug themselves deep into a hole. Unable to pay their loans, banks (usually large, Northern banks) would seize their collateral. This often meant the deeds to their farms. Those who were forecloses sought an ally against what they saw as ruthless capitalists.

In a sense, the large banks were ruthless sharks though when one fails to pay back their loan, then one is not entirely faultless. Sensing a means to gain at the poll, the Labor Party stepped in to help these dispossessed farmers. America’s own socialist party called itself Labor because the party bosses believed that ‘worker’s’ party invoked images of Red Revolution and that the term socialist was too European, too alien to suit the American mind set.

The Labor Party made its early gains by supporting organized labor in American factories and mines. They lost ground against the Progressive Party when the Progressives pushed for universal manhood suffrage, which with the passing of the 15th Amendment in 1897 became a reality. They lost again with the land redistribution scheme of 1916. As banks foreclosed on small farms they did not miss an opportunity to gain support.

The banks were the enemy, stepping on the backs of the poor to gain more and more wealth. Their rhetoric served as an anchor to gain votes in the North as well when veterans released from duty found it difficult to regain their old jobs. The war forced organized labor to bend for the benefit of the nation as a whole. Unions were as patriotic as any other organization and even more enthusiastic about restoring the Union and expanding their influence in the restored States. It did not occur to them in the war years to try and organize the replacement workers, millions of American women.

Factories wondered why they should accept the return of their former Union employees when they could keep their replacements, who made as low as 60% of the previous wages. Women wondered why they should give up their jobs. Married women often relinquished work in favor of their husbands. With 1.7 million Union dead, many women would never find husbands and had little choice but to work. They needed the income to keep their heads above the water in a turbulent world. Only the post-war boom, a surprising outcome sparred partly on by the demand of machinery down south, prevented the predicted Labor Party gains in the 1918 election.

In the occupied States, Labor and Progressive Parties made the biggest inroads, with the dividing line between the two seeming to be the same as between those who succeed in life and those who fail. At least that was how the Progressive Party would portray their rivals in the 1920 election. The Democratic Party opposed land redistribution in principle, though it did approval of punishing Southerners, as well as supported business saying that those who failed have mostly themselves to blame. The Republican Party was silent on the issue, with the RNC knowing there was little chance of them seeing a single federal level official elected in the South even after the States re-entered the Union.

Sunday, February 8, 2015

Saturday, February 7, 2015

10th Cavalry Regiment

Violence in the South was not confined to organizations such as the Sons of the Confederacy. Often, they were spontaneous riots of civilians in poorly garrisoned regions. One of the larger riots struck Jackson, Mississippi on August 8, 1918. One of the Freedmen’s Bureau’s pet projects was the establishment of schools for the children of former slaves. Even in States were Free Blacks were allowed to live, they were seldom allowed an education. In almost all cases, any education took form in what would now be called home schooling.

More than three thousand of Jackson’s White population showed out in protest, surrounding the refurbished barn on the outskirts of town that would serve as a school. With an unemployment rate of upwards to 25%, much of the city’s population had nothing better to do with their time than to heckle Northern institutions. Within this protest were members of the Mississippi Home Guard, an organization similar to the Sons of the Confederacy, though focusing more on racial purity than simply killing Yankees.

The MHG planned to torched the new school during an incited riot. It was hoped that the law in the city would either be too busy trying to reign in the rioters or be sympathetic to the Guard’s cause. What they did not intend was for a company from the 61st Ohio Guard to appear in the city. Upon hearing of a fomenting riot, the commander of the company had his unit surround the school. Over the menacing crowd, Captain Ed Howards ordered the crowd to disperse. Even as his machine gun squads began to set up the tools of their trade the crowd did not back down.

In hindsight, it was a very foolish move. The former Confederacy was under martial law and Mississippi was no exception. If anything, it was stricter than and in Alabama than any other occupied States. Howards had hoped to break it up peacefully, a hope that was shattered along with a bottle full of gasoline hurled at one of the company’s vehicles. Sensing it was under attack, the company opened fire on the crowd of civilians, killing two hundred seven of them.

It was a step to maintain order too far. Northern newspapers, long since supporting Reconstruction and the punishment of the South, denounced the Jackson Massacre and its butchering of unarmed civilians. Unfortunately, not a single Home Guard member was found among the dead. The official response from the Roosevelt Administration was that if rioters did not wish to be shot then they should behave themselves. Behind the scenes, he sought for means to prevent excessive violence. Bringing the South back into the Union was hard enough without a civilian populace completely hostile towards it.

The 10th Cavalry Regiment, the famed and feared Buffalo Soldiers, back on their horses occupied a piece of Mississippi centered around the small town of Tupelo. For many in the regiment, it was a homecoming of sorts. Of these soldiers, Captain Hiram Wellington returned to a land he had not seen in twenty years. He was born on a plantation not far from Tupelo in 1874. In 1889, he managed to successfully runaway from his plantation. After a hair raising odyssey northward, he managed to cross the international boundary and reach the land of liberty.

Though Kentucky was one of the United States, its government and elite were not overly fond of Blacks, especially escaped slaves. Populated largely by pro-Union Southerners who relocated north after the States’ War, the White populace saw him as trouble. The Black population saw him as competition. After two years working odd jobs, he enlisted in the Army where he was assigned to the “all-Black” 10th Cavalry. In 1891, only the enlisted personnel were all Black. It was not until the Great War, when NCOs earned battlefield commissions did Black soldiers become officers.

Wellington was one such man, earning a commission in early 1916, seven months after being awarded the Silver Star in the previous year. By the time Tennessee surrendered, Wellington earned the rank of Captain, the highest rank any Black soldier could achieve at the time. In command of a cavalry regiment, he helped confiscate plantations and free slaves, including the home of his former owner, Jonathan Wellington. Wellington, the White Wellington and his family left Mississippi after losing much of their wealth, opting to start over in Chile. Hiram Wellington led the eviction of his former owners, one of the high points in his life.

After the riot in Jackson, the Secretary of the Interior and the Attorney General urged Roosevelt to remove the 10th Cavalry from occupation duty. They feared the political firestorm that would erupt if Black soldiers were forced to gun down unarmed White civilians. Roosevelt conceded the point yet refused to simply yank the 10th off the lines. The unit held an exemplary war record and to pull them off duty would be bad for troop morale. He sought a means of getting them off the front lines of Reconstruction while saving face.

He came up with the idea of converting the 10th Cavalry from horses to engines. The Great War saw the armored vehicle supplant the horse and most cavalry units were gradually transition to mechanical mounts. He decided to convert the 10th. His plan met with resistance in the War Department with the Secretary of War reminding the President that an armored vehicle was considerably more sophisticated than a horse. The War Department and Army remained skeptical whether or not Black soldiers could handle machinery.

Roosevelt countered with examples of intelligent Blacks, such as George Washington Carver, a man who was born a slave and became one of the premier minds of the Union’s Black community. If a Black man could claim a number of inventions then surely one could be trained how to maintain an engine. Even with this argument, he still agreed to give the 10th the simplest of the armored vehicles, the M3 Jackson scout/light armored vehicle.

Withdrawal from Mississippi and redeployment at Fort Knox for training on the M3 was played for all its propaganda value. In the United States, ones ability counted for far more than one’s race, ethnicity or legal status upon birth. A few editorials, such as one in the New York Times, pointed out the timing of this reassignment. For the Freedmen of the South, it was sign of hope. One could achieve anything in the United States. Unfortunately, for them the United States was not Alabama or Georgia but Illinois, Ohio and New York. This reassignment saw the start of a gradual movement of the Black population northward.

Towards the end of his life, Wellington dictated his memoirs to a former reporter of the Chicago Tribune. Being born a slave and educated later in his life, Wellington was only semi-literate. He could read orders as well as any soldier though his writing skills were sorely lacking. His book ‘Born a Slave and Died Free’ was published posthumously in 1931.

Friday, January 30, 2015

Sons of the Confederacy

Not all veterans’ organizations in the South were filled with violent terrorists. One of the more legitimate and widespread organizations was called the Veterans of Confederate Wars. As the Confederate States participated in only one major war, their ranks were almost all Great War veterans. A few cavalrymen past their prime in 1913 were allowed to join. These old Indian fighters not only lent more legitimacy to the organization; they also brought with them new tales of warfare. Granted, none of them faced the meat-grinder of trench warfare but fighting on the old frontier was no less gruesome.

VCW also acted as a support structure, allowing soldiers to find jobs for their comrades and for the group as a whole to aid war widows and orphans. In the first winter following the war, the VCW was essential for staving off a potential famine. While small farmers were in no danger of starving, the people of the cities, who depended upon food harvested by slave labor, found the winter of 1916-17 to be hungry times. They were also cold times in the Upper South as not only was the limited electrical grid destroyed, there was also a chronic shortage of coal. Again, the VCW helped the needy.

Despite its obvious charity work, it still drew the suspicious eyes of the occupation authority. Anything with the word Confederate in its title was strongly discouraged. Most such organization were less than charitable. Of the numerous paramilitary organizations to sprout during Reconstruction, none were as destructive as the Sons of the Confederacy. This organization was founded by unreconciled veterans, chief among them the Georgian Earl Watson and Texan Leopold B. Jamison III. Their goal was not to aid the impoverished.

Their first appearance was recorded on April 15, 1918, when three hooded figures strode into a newly establish United States post office in Macon, Georgia and opened fire, killing seven. Of these, only one was a federal employee. The others were Georgians trying to ship packages. To the SOC, anyone using the federal government were collaborators.

Their favorite target were soldiers, Freedmen and the Bureau tasked with aiding them. In June 1918, fifty of the SOC engaged in a firefights with the US Army as it enforced the illegality of slavery. Taking down the plantation owners was an easy enough task. Their wealthy and large estates made them highly visible targets. The small farmer, the type that might own between three and seven slaves was another matter. Even two years after the way, not all of the backwoods farmers were tracked down and few of them voluntarily relinquished their property.

The SOC often came to the aid of these small slave owners, garnering great support among them though they fought a losing battle. Paramilitary with rifles and submachine guns were hardly a match for armored vehicles and soldiers angry of being posted so far from home after the war was supposedly over. The problem was most severe in Mississippi and Alabama. The June 1918 move to clean Lawrence county, Alabama saw more than a dozen such firefights on small farms. In only three of these attempts did the SOC have any success, temporarily driving back soldiers who were unprepared for a fight. As the month ground onwards, ambushes became less frequent and the Sons switched to softer targets.

They received little attention from Northern press as there were a great number of such groups dedicated to making restoration as difficult and costly as possible. In fact, few took them as a serious threat until August 1918, when they successfully bombed the Freedman’s Bureau in Selma Alabama. Sixty-four people were killed in the bombing, including Black civilians fleeing the burning building. Selma’s fire department refused to extinguish the flames, though if this was from support of the SOC or fear that they might be gunned down has not been established. The following day, soldiers searching the ruins found a message scrawl on a still standing wall. It read simply “the South shall rise again”.

Sunday, January 25, 2015

Rebels without a Cause

At the start of 1917, the war had been over for months. It appeared to the people of the North Carolina back country that some Confederate soldiers simply had not received the memo. Chief among these rebels was on Major Tom McPherson of the 102nd North Carolina, who took control of a regiment of the division and led it into the wilderness. From the Appalachians, his regiment raided towns and ambushed Union patrols. He caused so much trouble in 1917, that White Water ordered the entire XIII Corps to the region to deal with the problem.

The story of hunting down McPherson was retold time and again, its most famous incarnation being the 1956 movie Rebel without a Cause, staring actor and future President James Dean. If one believed the movie, the violence in North Carolina ended with the death of McPherson and the surrendering of his regiment on October 14, 1917–or rather most of the regiment. Not all surrendered. Squad and platoon sized elements escaped to continue the fighting.

Instead of attacking directly, they struck from the shadow, ambushing small patrols, robbing banks and trains and murdering off-duty soldiers. The problem grew so intense in the city of Winston, North Carolina that the commander of XIII Corps asked permission to take hostages in the city. White Water rejected the request, saying it had no worked for the Germans and it would not work here. Executing civilians at random would only drive civilians into the resistance. That was part of the holdout’s plans, one that never came to fruition. Southern civilians might not like the Yankee but they remained war weary after years of a losing war.

In Charlotte, renegades preyed on the occupation force, murderer soldiers off duty throughout the city, as well as killing any civilians viewed as ‘too close’ to the Yankees. By June 1917, it was unadvised for any soldiers to be out on the street in less than squadron strength, with platoon-sized patrols a regular feature in the city. Again, the random murders sparked a request for taking of hostages and again the request was denied. However, to allow the soldiers freer reign, Charolette was declared a city under siege. While under siege, the defenders of a city can take any actions they deem necessary, though hostage taking was explicitly forbidden.

Nonviolent, or rather no casualties attacks were also launched against facilities that aided the occupiers. In October 1917, renegades sabotaged one of US Steel’s newly acquired steel mills in Asheville. Attempts to organize the steel workers failed, at least attempts by the rebels. The Labor Party and its supporters would prove more successful in the following decades. Many Southerners, especially veterans, were so pleased to have any source of income that they dared not risk it. Without a paycheck, they could not care for their families, a consideration that does not apply to the largely single men of the resistance.

The organized military resistance in North Carolina ended in February 1919, when the last of the renegades were declared killed by XIII Corps. In truth, they killed only the last fighting soldier. Many other soldiers in the renegade regiment deserted, returning to their families after years from home. Others cast off their uniforms and continued the struggle in a different guise.

Tuesday, January 20, 2015

Recon. part 4

Redistribution of Wealth

To break the power of the Southern elite, the Roosevelt administration designed a two-prong attack. First, the plantations and land holdings of all slave owners (i.e. the wealthy who ruled the former Confederate States) was confiscated without compensation. Afterwards, the slave were freed and the land divided among several groups of people. The first choice to prime land was rewarded to veterans of the United States Army, or in the case of Cuba the United States Marine Corps. The parceling of land to veterans not only rewarded them for years of service but it also placed a very loyal demographic into the heart of the Deep South.

The second group to be rewarded land were the former slaves. In effect, those who worked the land now owned it. Parcels of land ranging from forty to one hundred sixty acres were rewarded to each slave family, depending on the number of dependents. The plots were smaller than those granted to veterans but equal to the size of the land granted to the third group; poor Southern Whites. This was simply buying the loyalty of the previously disposed poor voters of the Confederacy. It turned out to be a poor political tactic as most of Southern Whites voted for the Democratic Party once elections were restored.

The final party happens to be the most controversial at the time. Roosevelt and the Progressive Party decided to extend the offer to the Five Civilized Tribes. The Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole once lived in the Deep South. In April 1917, after safely re-elected, Roosevelt pushed for the repeal of the Indian Removal Act. It was strictly a symbolic act as United States law allowed Indians to live wherever they chose.

The Democratic and Republican Parties openly accused the Progressive of ‘stacking the electoral deck’ in the Deep South. The Labor Party made similar protests, though partly because they were unable to employ the tactic. Nonetheless, more than twenty thousand families with ancestral ties to the Five Tribes departed Oklahoma to take their forty or one hundred sixty acres of prime Georgia, Florida or Alabama land.

All this redistribution left the former plantation owners penniless and homeless, which was precisely what Roosevelt had intended. The punishment of the Southern aristocracy was more popular than what some viewed as socialist redistribution of wealth in more conservative and reactionary circles. A great many of the disposed left North America altogether, with more than half choosing Brazil as a place to begin a new, with another thirty percent opting for South Africa. The diaspora was not intended but nor did anyone in Washington try to stop it.

The States themselves were also wealthy land-owners. Unlike the Union, where politics and economics tend to be separate, the Confederate States partook in state capitalism. The individual States owned industries, and often monopolies within their borders. For the most part, these businesses were industrial in nature, such as munitions plants, foundries, shipyards and other strategically vital industries.

In the case of Cuba, the State owned a monopoly on liquor distribution (though manufacturing of alcohol was privately owned). The state-controlled rum industry was caused not by strategic necessity but for political reasons. The temperance movement was big in the Confederate States, with the Deep South (with the exception of Louisiana) outlawing the selling, manufacturing and transportation of alcohol within their borders. As Cuba was the largest producer of alcohol in the C.S.A., it was necessary for the State to control its flow as to not have it end up in Florida or Mississippi.

Starting in 1917, the Federal Government began to privatize the state-owned businesses. Unlike land redistribution, privatization was a process rife with corruption. In a repeat of the 19th Century spoils system, businesses were turned over to political favorites. The Southern arms industry was quickly partitioned between the largest weapons manufacturers in the United States, with Colt and Remington reaping the biggest rewards. The Norfolk Shipyards ended up in the pocket of U.S. Steel while notorious privateer Joseph Kennedy used his influence to gain control of Cuba’s liquor distribution network.

Kennedy was viewed as somewhat of a war hero in New England. The wealthy man purchased an old destroyer in 1913, a three-stacked, three hundred ten tonne ship. Kennedy, as well as a number of other wealthy adventurers, managed to convince Congress to grant them Letters of Marque. In 1856, European powers signed the Paris Declaration which outlawed privateering. To Britain, Kennedy and the like were little more than pirates and would hang if ever captured. As the United States and the Confederate States were not signatories to the agreement, privateering was still a legal activity by the time of the Great War.

Kennedy captured several Confederate and British freighters, hauling their prizes back to Boston to the cheers of the crowds. Kennedy, though he hated the British, focused mostly on Confederate commerce. They were softer targets and the Confederate Navy would view a privateer more as an enemy combatant and not an outright pirate. Confederate privateers preyed upon Union shipping throughout the war. Kennedy’s biggest success was in a duel with the Confederate raider Chicken Hawk. In a two hour duel, his ship crippled the Hawk, forcing the ship to surrender at a great cost to his own crew. Kennedy himself received wounds in the battle when pieces of shrapnel ricocheted around the bridge, scarring his face for life.

The business men swooped down on the South like a flock of vultures. The Southern press, once restored, labeled these Northerners Vulture Capitalists. Southern workers lost jobs as the new owners either fired them and replaced them with more politically reliable employees or sold off their grant for scrap, making themselves that much wealthier. The military governors in the South tried to stem the corruption as the rise of Southern unemployment was a cause of tensions. Generals argued that employed civilians were less likely to cause trouble. Unemployed civilians had nothing better to do with their time and tended to gravitate towards anti-restoration groups.

Tuesday, January 13, 2015

Recon- part 3

Reconstructed Governments

As per the terms of their surrender, be it individual State or Confederate Congress, the civilian government within the State was suspended and placed under military occupation. Each of the generals commanding the occupation sectors appointed a general to be military-governor of the reconstructed State. In order to assure a smooth transition back into the Union and a loyal government, each of the generals and their staff were given authority over who could and could not be in the new civilian governments.

The first to be reformed were the individual towns and counties. They seldom had much interference from military rule, save to bare certain individuals from public office. At the top of the list was everyone in the Confederate bureaucracy, both national and State level. Given the lack of skilled people able to take up running the States during the era, these restrictions were soon limited to the higher echelons of either tier of government.

Those in the lower tiers were forced to swear an oath of allegiance to the United States before they could even obtain permission to run for office of apply for employment with the elected official’s department. During the first few years of Reconstruction the number of Southerners attempting to obtain permission was small and primarily at the local level. At State level, seeking permission and swear allegiance to the United States was seen simply as collaborating with the Yankee. Few took the risk.

One who did was Colonel Christopher Fuller of the 77th Cuba Infantry. He fought against United States Marines in his home State for years and swore to his dying day that had the order been given, he would have fought them until his dying day. For too many of his comrades, such a proclamation turned out to be true, though their deaths were not at ripe old ages. Cuba, despite its large slave population in the 1860s, was always a rather reluctant member of the Confederate States.

Its succession convention was held by a handful of mostly self-appointed delegates who represented only the Anglo plantation owning elite. The Spanish plantation owners were divided on the issue and the Mestizo and Freedmen ranchers and small farmers, along with small White land holders were against succession. Many of the Whites took the Union up on the peace terms and resettled in the United States, primarily in Kentucky and Costa Rica.

Fuller was born in Jacksonville into the Anglo elite, though he took a Spanish wife and lived in strongly Catholic Santiago. His home was the first major Confederate city to fall to the Union when it, along with Guantanamo, were targets of the late 1914 invasion. He nor his wife owned any slaves and thus their home was spared the torch, though Marines did help themselves to its wine cellar.

Cuba had always been the oddball of the Confederate States. Its demographic made it the most liberal State, more so than Louisiana. It also was one of great contrasts. It retained slavery in the agricultural and tourist industries yet had the most liberal laws concerning freedmen. Free Blacks were allowed to own property, theoretically including slaves though few were known to have taken advantage of it. Though the land-owning Whites, Anglo and Spanish, dominated politics and government, there was a great deal of legal equality among the races. Enough so that Roosevelt once referred to it as the most egalitarian of the Confederate States.

This attitude would aid it greatly in returning to the Union as an equal among States. Fuller knew there was little point in resisting reunion and believed his fellow Cubans should put the past behind them and move forward. In order to run for office, he was forced to take the oath of allegiance, a process that he said afterwards left a worst taste in his mouth than the cheapest of gin. He was also limited to what political affiliation he could chose from the select granted to him by the USMC Governor-General, that being the four political parties of the Union.

Even after more than fifty years, no self-respecting Southerner would join the Republicans, the party of Lincoln. He also viewed the Labor Party as a thinly veiled platform for socialism. He respected the Progressive Party, for it was the party of Roosevelt and the party that defeated the C.S.A.. Because of the latter, he stayed away. This left him with the Democratic Party, which he found ironic. The US and CS both had their own native Democratic Parties and both followed similar ideologies.

His choice was more than for personal preference. Another similarity between the two government was that one candidate from each party was allowed to run for any given office. As a registered Democrat, Fuller was guaranteed election for the governorship as well as Congressional Representative and possibly Senator, depending on the make up of the State Assembly and that in turn would depend on how many of the recently freed slaves were allowed to vote. Black men had the franchise in the United States, mainly because they comprised less than three percent of eligible voters. Close to thirty percent of Cuba’s population was Black, making the political dynamics far different.

When he ran for office in 1924, when Cuba was declared reconstructed, handily winning a seat in the State Assembly for his district. From there, he continued to preach reconciliation as a veteran of the Confederate Army and as a citizen of the United States. He also fought against the corruption growing in Cuba both from organized crime and from vulture capitalists, with one of his greatest political enemies becoming the former Union privateer Joseph Kennedy, who used his political connections to muscle his way into the privatization of formerly Cuban owned industries.

Saturday, January 10, 2015

Reconstruction Part Two

Road Plan for Reconstruction

The road to fully restoring the Union would be a long and expensive one and the soldiers occupying the South would not be the only Americans discontent. The initial plans for Reconstruction came to life following the 1915 Battle of Fredericksburg, where a quarter of a million Americans on either side of the divide perished. Taking and holding the small scrap of land galvanized President Theodore Roosevelt as well as his Secretary of State and members of Congress into preventing a similar disaster from again occurring.

As Roosevelt was no fool, he knew the next war would use weapons even more powerful and lethal than the machine guns of the Great War. The only way to prevent a future war was to prevent two separate sides from occupying the same continent. It was an idea his administration toyed with since the war began. When war broke out in 1913, War Plans Gray and Red were activated. In each case, the objectives and how to defeat the enemy were discussed in great detail. What came afterwards was a matter the War Department did not plan.

Nobody in 1913 or 1914 would openly discuss restoration, though there was plenty of talk about regaining land lost to the British following the Second and Third Anglo-American Wars. As for concessions from the C.S.A. they ranged from indemnities to disarmament to cession of land. As 1915 rolled in, the question of how much cession would justify the loss of life. Following Fredericksburg, there could only be one answer to the question.

The war, indeed the previous five decades, were nothing less than a national tragedy. In the States’ War, brother fought brother. In the Great War, cousin fought cousin. Even the Canadians were viewed as wayward relations, though the quest to ‘conquer Canada’ was long since abandoned and any hopes of them peacefully merging with the United States long past. It was time for the American family to come back together.

In 1915, restoration was unthinkable to the Confederates. Their war aims were simple: survival. They had hoped for a quick defeat of Germany in Europe followed by an influx of British soldiers to aid against the Union. Even Canada was denied the level of aid Ottawa requested. With a population of seven million, Canada could not hope to stand up alone to the United States with its sixty million. Philadelphia knew this and decided to mark Canada as secondary in importance. The twenty-seven million Confederates concerned them greater.

Comparing populations between Union and Confederacy is always a bit of a problem. The Union has its entire demographic of men between the age of eighteen to thirty to draw upon. In the Confederate States, nearly one-third of their population is automatically discounted. Black soldiers were not part of Montgomery’s equation, not even freedmen volunteers. In the beginning of the war, they were bared from industries the same as women. Only the tremendous losses at the front changed the stubborn minds of Southerners, though only enough to permit Black men into occupation previous classified as White only.

Even halfway through 1916, the Confederates defiantly claimed to rather fight to the last man than rejoin the Union. Or rather that was the word of the Confederate Congress. By the middle of the year, Tennessee lay in ruins with Virginia and Cuba not in much better shape. With more than half his State already administered by the Union, Governor Harold Wilson sought any means to stem the tide. Requests for more soldiers from other States went unheeded. Even if his prayers were answered, Wilson doubted the Union could be kept out of Chattanooga and the industrial heart of eastern Tennessee.

His State already counted more than two hundred thousand among the dead, not including civilian losses. If his compatriots in the Confederate States could or would not aid him in the fight, he had few options in saving Tennessee. He had no option in evicting the Union. Even if restoration was never achieved in the Deep South, there was no way the Union would ever let Tennessee go when the war ended. No matter who won, Tennessee was under the Stars and Stripes.

With the fate of his State already decided, Wilson saw no reason why his people should continue to suffer. His momentous decision to seek a separate peace opened a flood gate. With Tennessee quitting, Cuba follow, then Virginia and even the whole of the Confederate West threw in the towel as a whole, leaving the Deep South alone to face a wave of destruction with nothing but disorganized State divisions wanting nothing more than to return home.

Once the Confederate Congress surrendered, the former C.S.A. was divided into three military sectors; west, central, east. The Eastern Sector consisted of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida and Cuba. To oversee the occupation, Roosevelt nominated General Clarence White Water, the man who commanded Second Army since 1915. The general from the State of Iroquois was a war hero in the eyes of all Americans, though perhaps not of the same level as Pershing or Arnold. For White Water it was a well earned post. For the former Confederates it was a calculated insult as the racially minded Southerners scoffed under the command of a general who was three-fourths Indian.

The Central Sector was granted to General John ‘Black Death’ Pershing. His virtual destruction of Tennessee saw the nickname Jack replaced by that of Death. Pershing held the position until 1919, when he decided to transfer to the Military Academy at Fort Arnold as an instructor in history. One of the Joint Chiefs famously grumbled upon hearing of Pershing’s transfer “great, now we’re going to have a whole generation of officers spouting nonsense about Gilgamish and Sargon.” Finding a successor was a great challenge. Samuel Arnold, self-styled Conqueror of Memphis, was the obvious choice. However, as with many in his family he stepped on the toes of politicians. Congress decided on an anyone-but-Arnold policy for command of Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas and Louisiana.

The Western Sector (Durango, Sonora, Chihuahua, Jefferson, Texas and Oklahoma) was placed under the command of a lesser known commander. Lieutenant General Charles Rhodes commanded XVIII Corps on the Colorado Front. The western part of the Great War received far less press than the massive body counts of the Ohio and Potomac Fronts. The war also lacked any solid front and consisted of large maneuver and sieges. Rhodes participated in the conquest of Nogales in 1913 and the Siege of Guaymas in 1915. The less populated West would prove much easier to reconstruct than the other regions.

Friday, January 9, 2015

Reconstruction, part one

A sample of one of my current projects. Reconstruction: The Roarings '20s.

Not Home by Christmas

Those hundreds of thousands of veterans who expected to be home by Christmas upon hearing of the Confederate States’ unconditional surrender on September 30, 1916, turned out to be sorely disappointed. Unlike previous wars, the United States did not quickly demobilize its army. It was an unprecedented move in the nation’s history and one explained by President Roosevelt during last minute campaigning in October.

Defeating the Confederate States was not enough. After a war that left millions of Americans dead on both sides, he and his administration, along with Congress, every soldier who shed blood and the families of the casualties were all determined that such a calamity should never again befall the American continent. Now that the Confederate Congress surrendered the Union still had a job to do; make sure the Confederate Army and the divisions of the several States complied.

Disarming more than eighty divisions took time, months in fact. Many soldiers who expected to return home as soon as the fighting ceased found themselves in exotic locations such as New Orleans, Montgomery, Macon or Pensacola disarming the States’ divisions. The Deep South was expected to be the most stubborn of the C.S.A.’s regions, given that the Upper South sued for peace in piecemeal and the West gave in as a whole. If there were to be unreconciled rebels, they would be in these States.

Or so the Joint Chiefs believed. They did not expect to see the 102nd North Carolina simply vanish. Out of the division, eighty-two hundred seventy-one soldiers took to the North Carolina back country, swearing to fight the invaders in what they hoped would be a costly and long-drawn guerilla war. The Army did plan for resistance, either by former soldiers or local civilians. To what extent and degree it would come was anyone’s guess.

Disarming the Confederate Navy proved a far easier process. With half of their Atlantic Fleet destroyed at the Battle of Grand Bahama, there was little for their navy to surrender. U.S. Marines took control of three battleships, the CSS Congress, Mississippi and crippled Sonora, as well as a battlecruiser squadron, six cruisers and a number of destroyers. Not all of the ship of the Confederate Navy ended up in Union hands. The captain of the CSS South Carolina ordered his ship scuttled rather than handed over to his life-long enemies. Other Confederate captains, mostly of cruisers and destroyers, followed suit.

As the Confederate Navy was under the control of the former central government, there was nobody the Federal Government could penalize for the loss of the war prizes. The same was not true about the Confederate Army. North Carolina suffered a complete suspension of all civil liberties until their holdouts surrendered. In Alabama, when a number of armored vehicles of an Alabaman division were unaccounted for (later discovered to be scrapped rather than turned over to the Union), the Union military governor levied a fine upon the county that was home to most of the division.

Not Home by Christmas

Those hundreds of thousands of veterans who expected to be home by Christmas upon hearing of the Confederate States’ unconditional surrender on September 30, 1916, turned out to be sorely disappointed. Unlike previous wars, the United States did not quickly demobilize its army. It was an unprecedented move in the nation’s history and one explained by President Roosevelt during last minute campaigning in October.

Defeating the Confederate States was not enough. After a war that left millions of Americans dead on both sides, he and his administration, along with Congress, every soldier who shed blood and the families of the casualties were all determined that such a calamity should never again befall the American continent. Now that the Confederate Congress surrendered the Union still had a job to do; make sure the Confederate Army and the divisions of the several States complied.

Disarming more than eighty divisions took time, months in fact. Many soldiers who expected to return home as soon as the fighting ceased found themselves in exotic locations such as New Orleans, Montgomery, Macon or Pensacola disarming the States’ divisions. The Deep South was expected to be the most stubborn of the C.S.A.’s regions, given that the Upper South sued for peace in piecemeal and the West gave in as a whole. If there were to be unreconciled rebels, they would be in these States.

Or so the Joint Chiefs believed. They did not expect to see the 102nd North Carolina simply vanish. Out of the division, eighty-two hundred seventy-one soldiers took to the North Carolina back country, swearing to fight the invaders in what they hoped would be a costly and long-drawn guerilla war. The Army did plan for resistance, either by former soldiers or local civilians. To what extent and degree it would come was anyone’s guess.

Disarming the Confederate Navy proved a far easier process. With half of their Atlantic Fleet destroyed at the Battle of Grand Bahama, there was little for their navy to surrender. U.S. Marines took control of three battleships, the CSS Congress, Mississippi and crippled Sonora, as well as a battlecruiser squadron, six cruisers and a number of destroyers. Not all of the ship of the Confederate Navy ended up in Union hands. The captain of the CSS South Carolina ordered his ship scuttled rather than handed over to his life-long enemies. Other Confederate captains, mostly of cruisers and destroyers, followed suit.

As the Confederate Navy was under the control of the former central government, there was nobody the Federal Government could penalize for the loss of the war prizes. The same was not true about the Confederate Army. North Carolina suffered a complete suspension of all civil liberties until their holdouts surrendered. In Alabama, when a number of armored vehicles of an Alabaman division were unaccounted for (later discovered to be scrapped rather than turned over to the Union), the Union military governor levied a fine upon the county that was home to most of the division.

Sunday, January 4, 2015

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)